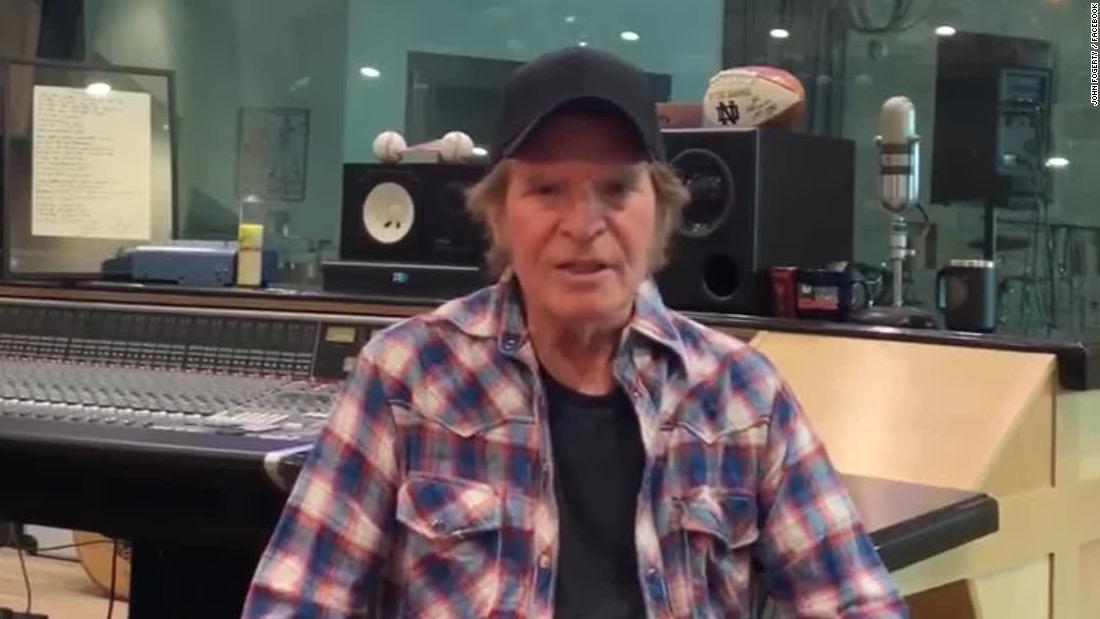

John Fogerty: ‘I had rules. I wasn’t embarrassed that I was ambitious’

He was once rock’s most consistent hitmaker. Then bitterness descended. Forty years after Creedence Clearwater Revival broke up, John Fogerty explains why things are finally looking up

John Fogerty would like to make it very clear that he is happy now. That needs spelling out because, for many years after the demise of his band Creedence Clearwater Revival, he was famous for being miserable.

For a short while, Creedence Clearwater Revival were the biggest band in America and, after the Beatles split up, the world. Between 1968 and 1972 they released seven albums and an unbroken string of hit singles, including Bad Moon Rising, Proud Mary and Who’ll Stop the Rain. Creedence were the only band who could unite hippies, rednecks and the pop critic of the New Yorker, not to mention younger musicians such as Joe Strummer and Bruce Springsteen, who later testified: “They weren’t the hippest band in the world, just the best.”

But their acrimonious split in 1972 marked the start of decades of legal strife, bad blood and creative paralysis. In fact, Creedence’s afterlife has been so painful and messy that they rival the Smiths as the most unreunitable band in rock, and Fogerty even became estranged from his own songs. He refused to perform them for another 25 years because the associations were too painful. If one of his old hits came on the car radio – which happened often – he would turn it off.

“When I was coming up I met so many rock’n’roll people from the first wave who were bitter,” he says. “I was 22 and I’d think: ‘Why is he so angry?’ You’d think with lots of hit records and success that you’d be very happy.” He pulls a face. “Of course, we both know that in a lot of cases that’s not what happens. In fact, showbusiness seems to be unusually full of folks who things go wrong for.”

A few days short of his 68th birthday, Fogerty at least looks undiminished by his tribulations. He still has the square-jawed, blue-eyed good looks of a Hollywood cowboy. He still sings in a mighty, bluesy roar, although his speaking voice has a quizzical, aw-shucks quality reminiscent of the actor Fred Willard. And he still wears the flannel workshirts he introduced to rock’s wardrobe 20 years before grunge – except he now sells them, too. On the table of his New York hotel suite sit two plastic-wrapped shirts, branded “Fortunate Son” after Creedence’s 1969 broadside against privileged kids who wriggled out of the Vietnam draft. “I suppose if you really thought about it that’s not a title you’d want to have,” he admits. “But it sounds great!”

The shirts are the brainchild of his second wife, Julie, who also suggested the idea for Fogerty’s new album, Wrote a Song for Everyone, on which he revisits his songbook with help from the likes of the Foo Fighters, Kid Rock, Tom Morello and Miranda Lambert. Most importantly, he says, meeting Julie in the late 80s rescued him from a ditch of resentment and despair. “I looked at life like a cat that’s been tasered. I was angry and hurt. I couldn’t deal with it. Julie truly transformed my life. It didn’t happen overnight but eventually all that good feeling forced out all the bitterness.”

Fogerty’s youthful ambition, class-conscious lyrics and craving for stability can all be traced back to his childhood in the California suburb of El Cerrito. After divorcing his alcoholic father, his mother was left to raise five boys alone on a teacher’s salary. John’s bedroom was in the basement and when it rained hard the room flooded, so he had to lay down planks of wood in order to reach his bed. “I didn’t starve or anything but I felt ashamed of my place. I didn’t want people to see my house.”

Fogerty first began playing with his older brother Tom, bassist Stu Cook and drummer Doug Clifford in a high school band, the Blue Velvets, when he was just 15. They signed to San Francisco independent label Fantasy Records, who rechristened them the Golliwogs and made them wear fuzzy white wigs to match their regrettable name. It’s perhaps for the best that their career was halted in 1966 when Fogerty was drafted into the Army Reserve. That was when he experienced his first songwriting epiphany.

“They’re marching you around all the time because they don’t know what to do with you,” he remembers. “I would become delirious and go into a trance. And I started narrating this story to myself, which was the song Porterville. I realised I could go anywhere and just make it up.”

After his discharge, the Golliwogs became Creedence Clearwater Revival and Fogerty began one of the most remarkable songwriting streaks that rock has ever seen. “I was very driven,” he says. “It was life and death. I could see we didn’t have a publicist, we didn’t have a manager, we didn’t have a producer, and we were on the tiniest label in the world, so we had to do it with music. And that kind of meant me.”

He describes his creative process in almost mystical terms. He would stay up late in his apartment, after his wife and baby had gone to bed, stare at a blank wall and let his imagination flow. “I was more like a book writer than a songwriter because I couldn’t make any noise. I think I accidentally discovered a form of transcendental meditation because it was so real.” He sighs wistfully. “I was the best I’ve ever been in my life.”

While Bob Dylan and the Band were turning to folk and country as antidotes to psychedelia, Creedence regarded rock’n’roll itself as the heartbeat of the nation: Americana you could dance to. Fogerty’s songs were so precise and direct that any halfway decent bar band could play them, yet they were enriched with compassion, moral clarity and a growing sadness that made his protest songs about Vietnam, class and the Nixon years some of the most powerful of their era.

They endure, too. Run Through the Jungle, an ominous warning about America’s gun culture, is as relevant as ever. When Fogerty revived Fortunate Son during the 2004 Vote for Change tour in aid of John Kerry, it sounded like it might have been written about George Bush himself, although it’s illustrative of Creedence’s broad appeal that Bush had several Fogerty songs on his iPod. “I really thought [the tour] had a chance,” says Fogerty, who was fired up by his opposition to the Iraq war. “I thought enough people had changed their minds since the first election. One night James Taylor said vote for the smart one!” He laughs. “Of course he was preaching to the choir.”

Fogerty wasn’t just Creedence’s sole songwriter but its producer and manager. By the standards of the time, he was unusually square (the closest he comes to swearing is “fricking”) and strait-laced. “Yes I was very disciplined,” he says. “Were there any drugs involved? Yeah, I smoked a little pot. I think my bandmates smoked quite a bit more pot. I had rules: never do that when we’re recording, never do that when we’re playing. To me it was a competition. You’d have the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane talking like: ‘We don’t want to be successful, maaaaan.'” He dismissively mimes a toke. “For one thing I wasn’t sure I believed them and for another, why would I go to all this trouble and only sell one record to my mom? I wasn’t embarrassed that I was ambitious. We wanted to be the best we could be.”

He still blames the Grateful Dead for ruining Creedence’s big moment at Woodstock. “They were snockered out of their minds! The Grateful Dead put half a million people to sleep and I had to go out and try to wake them up again.”

Fogerty’s Stakhanovite work rate made Creedence commercially unstoppable while wrecking his personal relationships. The track Wrote a Song for Everyone (“but I couldn’t even talk to you”) was inspired by a row with his first wife, who grew sick of playing second fiddle to the band. “A standup comic would say: ‘Well, at least I got a great song out of it,'” he says with a sad smile. “But I don’t look at it that way. I realised I had messed up. I got married at 20. There should be a law against that!”

Meanwhile, his bandmates grew to resent Fogerty’s control, and Fogerty became obsessed with escaping the band’s onerous contract. “What I clearly had an aptitude for was the music,” he says. “I knew exactly what to do. But the business part and the relationship part were not there at all. I mean woeful.”

Tom left in 1971 and the remaining trio dissolved the following year. In just five years Fogerty had achieved more than he could have imagined, only to see it unravel, and he was still only 27. This was the beginning of what he calls “the dark time”.

Fogerty realised that there was no way he could produce the mountain of material demanded by the contract, and only secured his freedom by surrendering ownership of his existing songs. Fantasy Records owner Saul Zaentz used these vast royalties to launch his second career as an Oscar-winning Hollywood mogul (Amadeus, The English Patient) while the band members, who lost millions of dollars in a bank collapse, struggled.

Fogerty’s war with Zaentz reached an absurd nadir in 1986 when Fantasy unsuccessfully sued him for plagiarising one of his own hits, the first time such a case had ever been brought. Shortly afterwards, he learned that his ex-bandmates had secretly sold their voting rights to Zaentz. Having led the band according to staunch principles – no compilations, no live albums, no syncs – he had to see them undermined one by one, and he was too sensitive and obsessive not to feel personally betrayed. “Before the fatal contract was signed I thought we were all in this thing together,” he says ruefully. “The fact that every one of those people could turn their back on me at some point was unthinkable.”

I can see why Fogerty’s principles might be easier to admire from a distance, and understand his ex-bandmates’ desire to move on, but the impact was devastating. Almost as soon as the band was over, he realised the songs no longer flowed like water from a tap. He’d never known where they came from, and when they no longer came he didn’t know where they’d gone. Despite managing a couple more iconic hits, 1975’s Rockin’ All Over the World and 1985’s Centerfield, he wasted long periods as a recluse, neither recording nor touring. During one hiatus Doug Clifford described him cruelly, though not inaccurately, as “Brian Wilson without the drugs”. “I was protecting the flame but I can’t say I was driven,” says Fogerty. “I wasn’t in any shape to do a good job.”

He still hasn’t forgiven Clifford and Cook, who continue to perform his hits as Creedence Clearwater Revisited, and his rift with his brother lasted until Tom’s Aids-related death in 1990. At the funeral, John said: “We wanted to grow up and be musicians. I guess we achieved half of that, becoming rock’n’roll stars. We didn’t necessarily grow up.”

“I was devastated,” Fogerty says of the falling out. “I was just crushed. The way I try to say it now is I didn’t feel very good, and when you don’t feel very good you don’t do things the way you’d do them if you were normal.” He has that tasered-cat look. “I was very confused.”

Fogerty turned some kind of corner in 1997 when he finally began playing Creedence material again and releasing solo albums with some regularity. He finds it hard to explain exactly what he was thinking and feeling in the long and testing period prior to that. At least former heroin addicts acquire the language to talk about the bad times but there is no rehab for bitterness and the suppressed anger still bubbles to the surface sometimes. After one long anecdote about some legal imbroglio, we realise we only have a couple of minutes left and Fogerty laughs awkwardly. “I stole a lot of time telling that really negative story.”

Perhaps he feels he has spent too much of his life telling negative stories and fighting unwinnable wars. It’s this context that makes Wrote a Song for Everyone more poignant and significant than most celebrity collaboration albums. It decisively reunites an extraordinary songwriter with the songs that, for too long, felt like strangers to him. So when Fogerty grins boyishly and describes the making of the album as a joyous experience, you can’t help feeling his joy is long overdue.

Leave a Reply