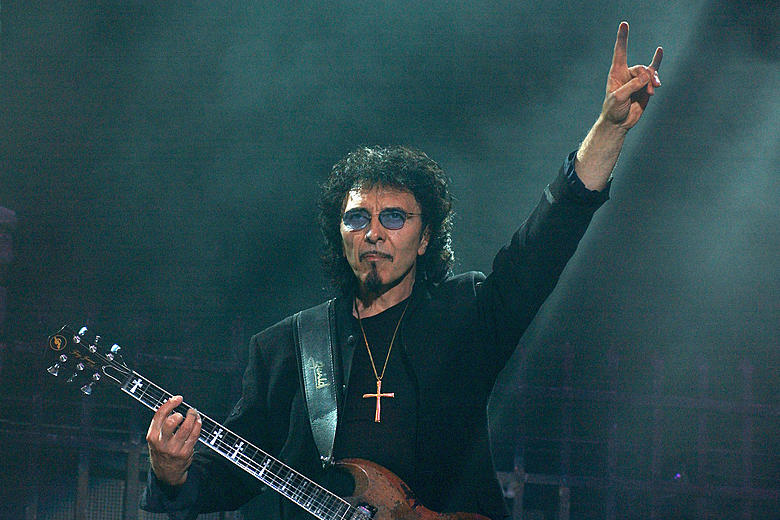

“It’s definitely an overlooked era,” begins Tony Iommi. “There’s people who don’t even know these albums exist!”

Mad as it seems, so far in this century, a sizeable piece of the Black Sabbath story has been unavailable as new. They’re not even on streaming services.

This week, with the release of the massive Anno Domini 1989–1995 boxset, and being made available digitally for the first time, “these albums” – 1989’s classic Headless Cross, the similarly epic Tyr from 1990, 1994’s Cross Purposes and the following year’s Forbidden – will see the light of day again.

It’s also a chance to appreciate the work of the man behind the mic on these records, Tony Martin. A previously unknown singer from Birmingham, he’d joined Sabbath during the recording of 1987’s The Eternal Idol, at a point when Tony Iommi was the last man standing from the original line-up, and not on his first, second, or even third search for a new singer.

Tony Martin, it turned out, was a rare find. With an enormous voice that soared higher than even his predecessor’s predecessor’s predecessor Ronnie James Dio, and a mystical lyrical quality that gave the music a dramatic flair and extra character.

It’s no exaggeration to say that The Tony Martin Era – interrupted in the middle by the return of Dio for 1992’s Dehumanizer – actually turned out some of the best music ever to bear the Black Sabbath name.

Headless Cross’ banging title-track for one, the devilish cautionary tale of When Death Calls for another, the mystical metal that makes up Tyr opener Anno Mundi for a third.

It’s also no exaggeration to note that they had more influence than is often given credit, most notably in the doom scene.

Watain singer Erik Danielsson, meanwhile, has previously enthused to K! that When Death Calls, to him, touches on an almost black metal quality in tone. “That lyric, ‘Don’t laugh in the face of death, or your tongue will blister and die,’ is just perfect.”

He’s not wrong. And even though Tony Iommi has often voiced displeasure at how Forbidden turned out, largely because of the production, it’s only right that it all gets a chance to stand up and be counted alongside everything else from The Greatest Band Ever To Do it.

Here, Tony Iommi looks back on Sabbath’s lost era, and the resurrection of some of their best work…

How’s it been revisiting these albums that have been left in the past for so long?

“It’s been really good, because over the years I’ve been asked by a lot of fans – when we were doing shows or whatever – about the Tony Martin era.

‘Why’s it got buried?’ We were touring with either Dio or Ozzy, or recording, or whatever it might be, so we were doing something else, and the focus wasn’t on [this] era. So now, it’s great to be able to sit back and say it’s finally going to come out.

Because it has been a bit frustrating. It was an era that that sort of got lost. And it’s a shame because there’s some great music on those albums.”

It does feel like a lost era of the band that a lot of people don’t even know exists…

“It really is. We were on IRS records, which is another story, and over the years this stuff got lost.

And at the time when they came out originally, it was a difficult time all around in the music scene. So now there’s people catching on to it, which is amazing, all these years later.

People didn’t know of this period, and they’re listening to it for the first time saying, ‘Yeah, we love it.’ I mean, there’s obviously people that don’t like it. But that goes with everything, doesn’t it (laughs)?”

How did Tony Martin come into the picture?

“Well, my best, oldest friend from school, Albert Chapman – who I’ve known since we were, like, 10 years old – managed one of the bands Tony had.

And when it came that we were looking for a singer, Albert says to me, ‘Why don’t you try Tony?’ We tried him and it worked out. I really liked his voice. And that was it, really. And there he was, stuck with us for 10 years!”

By the time of Headless Cross, other than you it was a completely new band from the ’70s and early ’80s. What effect did that have on writing?

“Well, I mean, Tony’d got a voice, he could sing all the various eras of Sabbath, so he was a bit of a variation. So when we came to writing albums, it was a new thing again.

Cozy Powell [drummer] was on board then, which was great. He was a real ally for me, because he’s from the same era and we we’ve known each other ever since the very early ’70s, and it was great to have somebody with you who’d been about and was established and had that credibility. And we had Neil Murray [bass] as well, so it all worked out and fitted great.

“For me, on the musical side, I was writing the same as I always did, just with different people. What Tony was doing lyrically and vocally was obviously a different thing, because he didn’t want to do what Ozzy had done, and didn’t want to do what Dio did, he wanted to create his own thing.

So he went off and started doing stuff like he did on Tyr, more Nordic. He wanted to make his own thing and not rely on somebody else’s past. And he really pulled it off.”

What were the writing sessions like?

“Cozy Powell would come to stay with me. We’d have a cassette player, and we’d sit down and start playing bits and bobs.

We’d have a few drinks, and more drinks, and more drinks. And before you knew it, we were coming up with ideas and putting them on tape.

And then we got Tony Martin over and played some stuff to him, and built it up like that. Then we got into a rehearsal room and started playing. It’s the same sort of thing as I do now, really.

I’ll come up with riffs and wait to see if somebody goes, ‘Oh, I like that,’ or, ‘I don’t like that.’ I like to have other opinions. So it was the same way of working for me, how I’ve always done it.”

Were you worried about what people might think of bringing in more new people to the band?

“I mean, it’s really difficult to bring new people into Sabbath. And it always has been, because you get the hardened fans that just won’t see anything different from the original line-up.

And then you get other ones that will accept new things, like when we brought Dio in. But that was different, because he was established, he’d done Rainbow and various other stuff.

Now here we were, bringing in Tony Martin, who nobody really knew. So it was very hard, and very hard for the fans to understand it.

Because there’s a complete new line-up of people that that weren’t a part of Sabbath before. So it was hard. It was very hard. But as I say, people have sort of accepted it now.”

What were your expectations, bringing in new people? That’s big shoes to fill…

“Yeah, definitely. When I brought in Tony, I expected too much from him, really, because it’s bloody difficult to have to stick somebody in front of a known band like Sabbath.

You expect them to be like the other people [in the band] have been: experienced. But of course, he wasn’t. He hadn’t played in those sized venues. And it must have been petrifying for him, really.

But it didn’t sink in for me at the time how hard it was for him. I mean, he really did pull things out of the bag, and it’s probably good for him to push him, but at the same time, we did throw him in at the deep end.

Obviously I get it now, but I didn’t at the time think how it must have been petrified standing in front of thousands of people.

“It’s hard to bring in new people and make it work. But in a way it’s quite good. I’ve never not been in Black Sabbath. I’ve always been in Black Sabbath. And it’s just unfortunate that as time went on, people have left or whatever.

But it’s sort of good, really, because it made us not rely on thinking, ‘Oh, it’s Black Sabbath.’ It made us work again, it gave us a challenge to actually do something with somebody else and make it popular.”

What was the expectation from the label at the time?

“Well, we had two or three labels that wanted to sign me in them days. Obviously I was offered better deals than what IRS had offered me. But the thing that I was concerned about was the interest from the record company, not the money.

And [label owner] Miles Copeland said, ‘Look, you know how to write stuff, you do it, that’s your department. You do it and we’ll support it.’

And I loved that idea, instead of being with a record company that says, ‘You’ve got to go more commercial, you’ve got to do this, you got to do that.’

I didn’t want any of that. So IRS, although they weren’t big, and their finances weren’t as much as the others, that’s the one I wanted to go with. I could do what I know how to do. And they supported it.

“But the problem was, IRS weren’t big enough. And so when we actually got out on the road, and certainly in America, it was tough, because it didn’t have the distribution.

People didn’t even know we had a record. And it was great in Europe because we had EMI. But with IRS, it was it was difficult, because they were a small label. So, it was hard.”

Leave a Reply