Rock biographer Philip Norman: ‘It took me years to understand the paradox of George Harrison’

George Harrison died on 29 November, 2001 after a four-year battle with cancer, aged 58. The 9/11 atrocities were only two months earlier but despite the continuous grim developments from the still-smouldering wreckage of New York’s World Trade Center and President George W Bush’s retaliatory “war on terror”, his passing leapt to the top of television news and into banner headlines.

Even at such a time, there were no complaints of trivialisation; the Beatles had long ago ceased to be just a pop group and become something like a worldwide religion. And, sombre though the TV or radio coverage was, it included generous helpings of music that, 30 years after their breakup, still had undiminished power to charm and comfort. Inevitably, it awoke memories of John Lennon’s murder in 1980 – but the two tragedies differed in more than their circumstances. That horrifically sudden obliteration of John seemed to have half the human race in tears at what felt like the loss of a wayward but still cherished old friend.

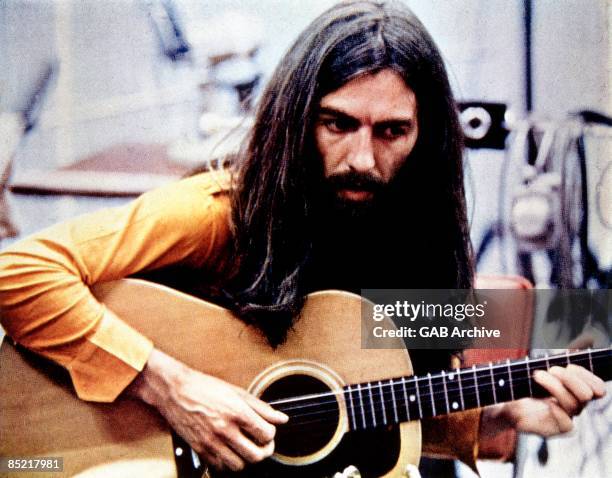

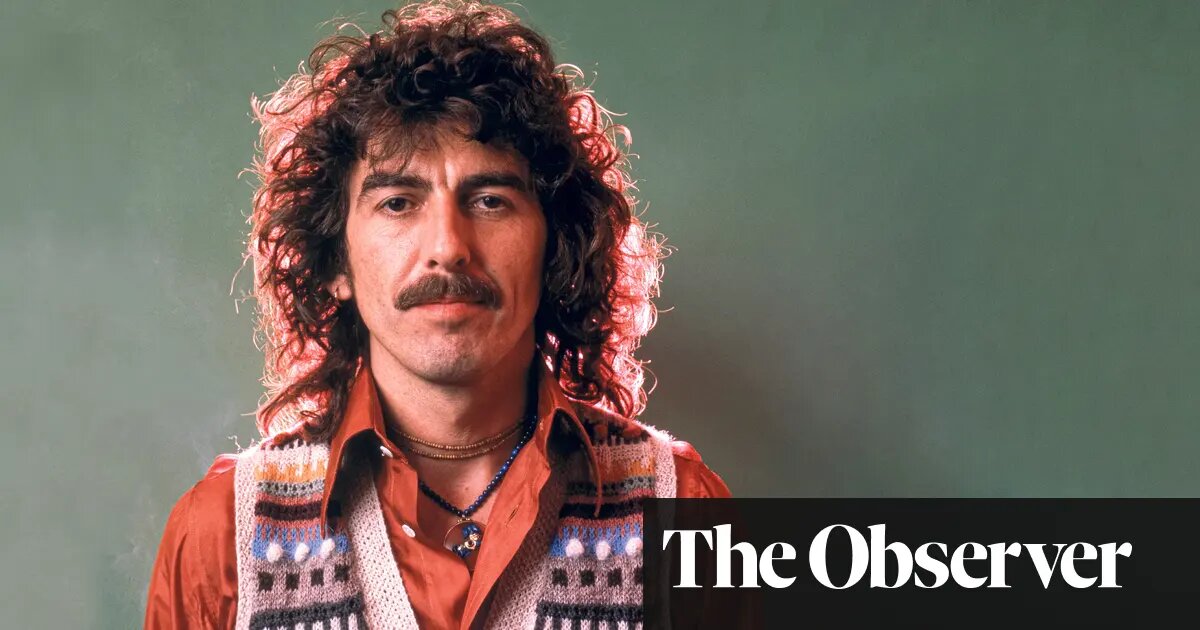

With George, struck down by a quieter killer, millions could mourn the musician, but there was much less to go on in mourning the man. For no more private person could ever have trodden a stage more mercilessly public. In later years, he’d taken to calling himself “the economy-class Beatle”, not quite joking about his subordinate status from the day he joined John and Paul McCartney in the Quarrymen skiffle group. Yet by dogged persistence, he made it into the first-class cabin with songs equalling the best if never the vast quantity of Lennon and McCartney’s: While My Guitar Gently Weeps, Here Comes the Sun, My Sweet Lord and his masterpiece, Something.

As a guitarist, he indisputably belonged in the 60s pantheon of six-string superheroes alongside Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix, Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page, while never rating himself more than “an OK player”. Alone in that company, he had a serious turn of mind; the Beatles, then commercial pop as a whole, radically changed direction after his discovery of the sitar and espousal of Indian religion and philosophy. For a few twanging months, any band with hope of chart success had better throw in a mini-raga.

Amid the mayhem of Beatlemania, no one would have taken him for an underdog. In live shows, he was adored almost as frantically as Paul with his fine-boned face, beetling brows and hair so thick and pliant that – as a Liverpool schoolfriend enviously said – it was “like a fuckin’ te-erban”. But the fine-boned face could be noticeably economical with the carefree grin his fans expected at all times; indeed, it first planted the amazing thought that being a Beatle might not be undiluted heaven.

This was the endlessly self-contradictory “quiet one”, actually as verbally quick on the draw as John at press conferences; who accepted the workhorse-role of lead guitarist, poring dutifully over his fretboard while John and Paul competed for the spotlight, yet offstage was the most touchy and temperamental of the four; who railed against “the material world”, yet wrote the first pop song complaining about income tax; who spent years lovingly restoring Friar Park, his 30-room Gothic mansion, yet mortgaged it to finance his friends the Monty Python team’s Life of Brian film; who, contrarily, became more uptight and moody after learning to meditate; who could touch both the height of nobility with his historic charity Concert for Bangladesh and the nadir of sleaze in his casual seduction of Ringo’s first wife, Maureen.

His obituaries agreed his finest post-Beatles achievement to have been All Things Must Pass, the 1970 triple album largely consisting of songs that John and Paul had rejected for the band or that George hadn’t submitted, anticipating their indifference. Its defining track, My Sweet Lord, was an anthem for any creed a year before John’s Imagine, with a slide guitar motif like a tremulous human voice that would become a signature as personal and inimitable as Jerry Lee Lewis’s slashing piano arpeggios or Stevie Wonder’s harmonica. It far outsold Lennon’s and McCartney’s respective solo album debuts and has continued to do so ever since: an unextinguishable last laugh.

His second wife, Olivia – an inconspicuous presence until the night in 1999 when she saved him from becoming the second Beatle to be murdered – issued a statement on behalf of herself and their son, Dhani, urging his fans to try not to grieve too much. He’d have wanted them to be as positive as he was throughout his dreadful illness, Olivia said, for the Hindu precepts he lived by had banished all fear of death. “He gave his life to God a long time ago. George used to say you can’t just discover God when you’re dying… you have to practise. He went with what was happening to him.”

Still, across every culture and in every language, the same chilling thought will have occurred, often to somebody born after – in many cases, decades after – the Beatles broke up: “Only two of them left.”

It has taken me a good few years to get around to writing a biography of George, and some people, I know, will be wishing I hadn’t. For, alas, his obituarists in 2001 included myself. At that point, almost everything I knew about George had gone into my 1981 Beatles biography, Shout!, which ended with the band’s breakup and barely mentioned their respective solo careers. Having to write 3,000-plus words on a deadline left no time for further research or reflection; I therefore judged him solely on his years spent with Ringo in an obvious second division from which he so often signalled impatience and discontent.

Leave a Reply